Health

The rise of the sleep data nerds: ‘The harder you try, the harder it is to sleep’

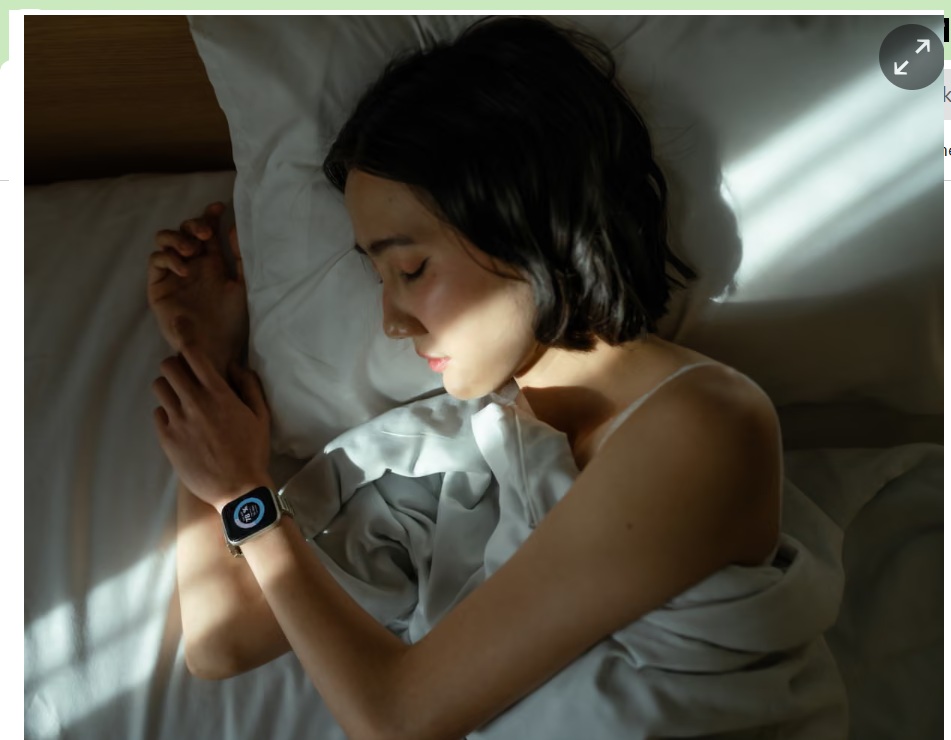

he first thing Annie and her partner do when they wake up in the morning is ask each other how well they slept. “And I literally say, ‘I’m not sure yet, let me check,’” – and Annie, a chief people and safety officer, reaches for her smartwatch.

Annie started monitoring because she worried she wasn’t getting enough good-quality sleep. Now she’s a self-confessed sleep data “nerd”, mining her sleep data for insights into her general health and wellbeing, using it to inform lifestyle decisions and even occasionally to guide how much she aims to accomplish in a day.

Sleep monitoring is a boom industry, mirroring what devices and apps such as Fitbits and Strava have done for physical activity. Market reports vary on the value of this industry, but it is clearly lucrative and growing rapidly. A quick search reveals a wide range of devices – rings, headbands, watches and other wrist-worn devices, under-mattress devices and bedside devices – all suggesting their use will unlock such quality sleep as to make Rip Van Winkle jealous.

An estimated 40% of Australians are not getting enough good quality sleep, and one in 10 experience chronic insomnia. “We do know there are a lot of people who do worry about their sleep and whether they’re getting enough sleep, particularly if they’re not meeting some of the recommended sleep duration guidelines,” says Dr Hannah Scott, a senior research fellow in sleep psychology at the Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute in Adelaide, and co-inventor of a wearable device that tracks and treats chronic insomnia

Scott sees the rise in the use of sleep trackers as generally good news. “They’ve certainly improved awareness around the importance of sleep and around healthy sleep patterns so overall, I’d say they’ve probably had a positive effect.” But there’s a downside. “If you try harder to exercise, you’ll become fitter, but we have the opposite problem with sleep actually; that the harder you try, the harder it is to actually obtain sleep,” Scott says. “We can be creating some problems over people becoming too obsessive about trying to optimise it.” There’s even a term for it: orthosomnia, which describes an unhealthy preoccupation with sleep-tracking data.

The most accurate picture of sleep health is derived from what’s called polysomnography, which requires a person to spend the night in a sleep laboratory with their head and body covered with electrodes that monitor and measure brain wave activity, eye movement, breathing, heart rate, muscle movement and blood oxygen levels. That provides a wealth of information such as time spent in different stages of sleep, how many times someone wakes up and how long it takes them to fall asleep, says Prof Christopher Gordon, professor of sleep health at Macquarie University in Sydney.

“Wearables – and that’s lumping a lot of different devices in one word – but generally they’re not that accurate at being able to tell how long you took to fall asleep and how long you’re awake and asleep overnight, and that’s because it’s not measuring brainwave activity,” he says. That brainwave activity is used to determine time spent in different stages of sleep: stage one, two and three of non-REM sleep and REM sleep

What wearables can detect and measure – in varying combinations and with varying degrees of accuracy – is heart rate, temperature, movement and blood oxygen levels, which are then fed into algorithms that determine whether the picture painted by that data is of someone sleeping soundly or restlessly awake. “It could be a device that’s specifically measuring movement only, and it’s looking at algorithms that say if your arms are moving a lot you’re awake, if it’s not moving a lot it’s sleep,” Gordon says. But “that has very little agreement with what happens in your brain in terms of the qualitative aspect of sleep”.

The other challenge is that there isn’t a clear understanding of exactly what good sleep looks like, says Associate Prof Jen Walsh, director of the Centre for Sleep Science at the University of Western Australia in Perth. “It’s an area that’s debated within our profession,” she says. There’s sleep quantity – simply the amount of time spent asleep – and sleep quality, which is more complex and takes into account time spent in different stages of sleep, whether sleep is broken, how often and for how long. “Sleep quantity is quite easy to define and calculate, whereas sleep quality is somewhat harder,” she says. Current guidelines suggest adults should aim for between seven and nine hours of sleep a night but there isn’t such clear advice on what type of sleep – how much of each stage – is optimum.

Sleep quality is also highly subjective and sometimes doesn’t match what even the most accurate lab-based monitoring says, according to Dr Maya Schenker, a postdoctoral researcher on trauma and sleep at the University of Melbourne. “If we feel like we slept very badly, it doesn’t matter what the watch is telling me,” she says. Even in people with chronic insomnia, sleep often looks a lot better on the polysomnography than what they subjectively report.

Rachel says her sleep-monitoring ring has helped her to understand some of the factors that help her get a better night’s sleep. “If I do pilates in the evening, I seem to mostly sleep better,” the Canberra-based public servant says. And Annie has noticed that if she has a glass of wine at any time in the evening, her heart rate during sleep is about 10% higher.

This is where most experts see the usefulness of sleep trackers in a consumer setting: helping people understand how their lifestyle habits and behaviour affect their sleep, and making changes to improve it.

“A lot of people are interested in changing their sleep habits, but it’s hard to find a place to start,” says Dr Vanessa Hill, a sleep scientist at the Appleton Institute at CQ University in Adelaide, who also consults for Samsung Health. Data alone isn’t generally enough to change behaviour, but “if your watch can send you a notification where it’s like, ‘hey, yesterday, you went on a walk at this time and it improved your sleep’, or ‘yesterday you stopped drinking caffeine around this time’ or whatever, and that helps you fall asleep faster”, that can motivate people to change, she says, “I think that’s the best potential that these kinds of trackers can have.”

Stop counting sheep – and 13 more no-nonsense tips for getting back to sleep

Hill uses a smartwatch and a ring to monitor her sleep, and says she does check her sleep scores – particularly her heart rate during sleep, which she says may predict oncoming illness – as soon as she wakes up. “I look at what they’ve been overnight, because if I am getting sick or getting a cold or something like that, my heart rate variability will actually tell me before I feel any symptoms myself,” she says. “If, for whatever reason, I have really bad heart rate variability one night, I’m just like, I need to take it easy today, something’s up with my body.”

Many experts stress that consumer sleep trackers are not diagnostic tools and have some important limits. “If you train an algorithm on a set population that is healthy, you’re not going to necessarily pick up the same signal out of a population with, say, peripheral vascular disease with reduced blood flow into the fingers,” says Dr Donald Lee, a respiratory at sleep physician at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research in Sydney. Sleep habits also change over the lifespan, which may not be reflected by the algorithms used.

However sleep trackers do provide an opportunity to encourage healthier sleep habits, Lee says. “If we can engage people to … go to bed with a purpose, to turn out the light and go to sleep and improve their sleep habits by engaging in the conversation, it’s a good thing for the health trackers to be doing.”

Health

Safe Blood Donation Before, During, and After Ramadan – Medical Guidelines by Dr. Ganesh Dhanuka

By Dr. Ganesh Dhanuka

Specialist Internal Medicine and Nephrology

International Modern Hospital

Blood donation remains one of the most impactful humanitarian acts, capable of saving multiple lives with a single unit of blood. However, during the holy month of Ramadan, many individuals question whether it is safe to donate while fasting and how to properly prepare for donation.

From a medical standpoint, blood donation is generally safe for healthy individuals. Nevertheless, appropriate preparation — especially in the context of fasting — is essential to minimize risks such as dizziness, dehydration, or hypotension.

This article outlines evidence-based recommendations for blood donation before, during, and after Ramadan, along with its physiological, psychological, and societal benefits.

Preparing for Blood Donation Before Ramadan

Proper preparation significantly reduces the risk of adverse effects during donation. Individuals planning to donate should:

Nutritional Preparation

Consume a balanced meal rich in iron and protein approximately 2–3 hours before donating. Iron-rich foods such as lean red meat, spinach, lentils, beans, and fortified cereals help maintain adequate hemoglobin levels. Protein supports plasma volume and recovery.

Avoid donating on an empty stomach, as this increases the likelihood of lightheadedness and vasovagal reactions.

Hydration Status

Adequate hydration is critical. Donors should:

- Increase water intake the day before donation.

- Drink extra fluids on the day of donation.

Proper hydration helps maintain blood pressure and reduces the risk of fainting.

Sleep and Lifestyle Factors

- Ensure 6–8 hours of quality sleep the night before.

- Avoid alcohol for at least 24 hours prior to donation.

- Refrain from strenuous physical activity before donation.

Medical Disclosure

Bring valid identification and honestly disclose:

- Any chronic medical conditions.

- Current medications.

- Recent illnesses or procedures.

Transparency ensures donor safety and protects recipients.

What to Expect During Blood Donation

The blood donation process is generally straightforward and takes about 10–15 minutes for the actual collection.

During donation:

- Stay calm and breathe normally.

- Avoid sudden movements.

- Inform medical staff immediately if you experience dizziness, nausea, sweating, blurred vision, or weakness.

- Follow all staff instructions carefully.

Most temporary reactions, when they occur, are mild and resolve quickly with rest and hydration.

Post-Donation Care and Recovery

The post-donation period is crucial for safe recovery.

Immediate Aftercare

- Rest at the donation center for 10–15 minutes.

- Accept fluids and light refreshments provided.

- Avoid standing up abruptly.

The Next 24 Hours

- Increase fluid intake significantly.

- Consume iron-rich foods to replenish red blood cell production.

- Avoid heavy lifting for 24 hours.

- Avoid strenuous exercise on the same day.

- Avoid alcohol for several hours after donation.

If dizziness occurs, lie down and elevate your legs until symptoms resolve.

Food

Foods That Look Healthy for Weight Loss (But Actually Aren’t)

By Dr. Yara Husein (Food and Nutrition Expert)

Companies often use specific buzzwords on food labels to market products as healthy and weight-loss friendly options. In reality, these options can sometimes have the opposite effect. Here are some common foods and drinks that might be holding you back:

Fat-free dairy products

Many think that fat-free dairy products are ideal for dieting and do not contribute to weight gain. However, in truth, these products can cause weight gain because fat-free products are less satiating than their full-fat counterparts; fat is a nutrient that supports feelings of fullness and makes food more enjoyable. Furthermore, food manufacturers often replace fat with sugar in low-fat and fat-free products to compensate for the lost flavour. Beyond that, skimmed dairy products provide the body with fewer nutrients than full-fat products, because vitamins such as A, D, E, and K are fat-soluble vitamins that require fat to enter the body, be absorbed, and be utilized.

Gluten-free foods

While it is essential for people with gluten-related disorders to avoid gluten, gluten-free foods are not necessarily healthier than foods containing gluten. Some processed gluten-free foods and desserts contain the same amount of calories and added sugar—if not more—as other snacks. Studies, including a study published in the journal PeerJ, indicate that gluten-free snack foods tend to be lower in protein, fiber, and certain vitamins and minerals compared to their gluten-containing counterparts. They are also generally more expensive.

Breakfast cereals

Many people think that breakfast cereals are an ideal and healthy breakfast to start their day, but in reality, many cereals are made from refined grains that lack nutrients like protein and fiber, and they can contain a high percentage of added sugar. For example, Honey Nut Cheerios, which are marketed as heart-healthy, contain 12 grams of added sugar per cup. Eating large quantities of these and other cereals high in added sugar may lead to an increased risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, high triglyceride levels, and weight gain.

Energy and sports drinks

Companies market sports and energy drinks as ways to boost energy and athletic performance, but these drinks can contain a massive amount of sugar. Consequently, they can contribute to weight gain for people who consume them without performing intense physical exercise. For instance, a popular energy drink like Monster (473 ml) contains 54 grams of added sugar—a quantity much higher than the amount recommended by the American Heart Association (25g for women and 36g for men). Research, including a study published in the journal Pediatric Obesity, has linked the consumption of sweetened beverages to health problems, including high blood pressure, fatty liver, and obesity in children and adolescents.

Diet soda

When following a diet, many people may turn to sugar-free or calorie-free drinks, thinking they contribute to weight loss. However, studies indicate that diet soda may contribute to certain health problems by altering brain responses to food and increasing the desire to eat high-calorie foods such as sweets and fast food. A study published in the journal Nutrients linked the consumption of these drinks to a higher risk of metabolic syndrome, which is a group of symptoms that include increased belly fat, blood sugar, blood pressure, and blood lipid levels.

Health

Excessive Screen Time in Children: Digital Eye Strain, Myopia Risk, and Long-Term Vision Health

By Dr. Tahere Rezaei

Ophthalmologist

International Modern Hospital Dubai

In today’s digital era, children are spending unprecedented hours on tablets, smartphones, and social media platforms. From a clinical perspective, the impact of excessive screen exposure on pediatric eye health is becoming increasingly evident.

Ophthalmology clinics are witnessing a clear rise in complaints linked directly to prolonged device use. Children often hold screens very close to their eyes and remain intensely focused for extended periods without taking breaks. This sustained near work places continuous strain on the visual system, particularly on the eye muscles responsible for focusing.

The most immediate and common consequence is digital eye strain. Symptoms typically include:

- Headaches

- Eye fatigue

- Blurred vision

- Burning sensation

- Dryness due to reduced blinking

When children concentrate on screens, their blink rate significantly decreases. Reduced blinking leads to tear film instability, which contributes to dryness and irritation. Over time, persistent strain can affect visual comfort and academic performance.

Rising Concern: Childhood Myopia

Beyond temporary discomfort, there is a more serious long-term concern — the increasing prevalence of childhood myopia (short-sightedness).

Extended near work combined with limited outdoor exposure has been strongly associated with faster progression of myopia. Natural daylight and distance viewing play a protective role in visual development. When children spend most of their time indoors focusing on close objects, the eye adapts by elongating, leading to blurred distance vision.

Early-onset myopia is not simply about needing glasses. Higher degrees of myopia later in life increase the risk of:

- Retinal detachment

- Glaucoma

- Myopic macular degeneration

- Early cataracts

Preventing rapid myopia progression during childhood is therefore critical for long-term ocular health.

Screen Use and Sleep Disruption

Another clinically observed issue is the effect of screen exposure before bedtime. Blue light emitted from digital devices can suppress melatonin production, disrupting the natural sleep cycle. Poor sleep quality affects not only overall health but also visual comfort, concentration, and cognitive performance.

Children who use screens late at night frequently report:

- Difficulty falling asleep

- Morning eye discomfort

- Increased fatigue during the day

Sleep plays a vital role in ocular surface recovery and overall neurological health.

Supporting Healthy Visual Development

For optimal eye development, children require balanced visual habits. Key preventive measures include:

- Limiting continuous screen time

- Encouraging daily outdoor activity

- Maintaining proper room lighting

- Ensuring appropriate screen distance

- Practicing scheduled visual breaks (such as the 20-20-20 rule: every 20 minutes, look at something 20 feet away for 20 seconds)

Parents play a crucial role in modeling healthy screen behavior and establishing structured digital routines.

As Dr. Tahere Rezaei emphasizes, eye health in childhood directly influences long-term vision outcomes. Early awareness, prevention, and regular eye examinations are essential to protect children from avoidable visual complications in adulthood.

Healthy eyes today mean clearer vision for life.

-

Discover1 month ago

Discover1 month agoIs February 2026 really a once-in -283-years MiracleIn?

-

Football2 months ago

Football2 months agoAlgeria, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire win AFCON 2025 openers

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoBascom Palmer Eye Institute Abu Dhabi and Emirates Society of Ophthalmology Sign Strategic Partnership Agreement

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoNMC Royal Hospital, Khalifa City, performs rare wrist salvage, restoring function for young patient

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoEmirates Society of Colorectal Surgery Concludes the 3rd International Congress Under the Leadership of Dr. Sara Al Bastaki

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoBorn Too Soon: Understanding Premature Birth and the Power of Modern NICU Care

-

Football3 months ago

Football3 months agoGlobe Soccer Awards 2025 nominees announced as voting opens in Dubai

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoDecline in Birth Rate in the UAE