Books

Read this and you will be happier

Find love

Chosen by Philippa Perry

Amir Levine’s Secure, to be published in April, is grounded in attachment theory, in which there are four main styles of bonding: anxious (craving closeness, but fearing rejection), avoidant (preferring independence over closeness), fearful avoidant (a mix of the two), and secure (comfortable with closeness and easy-going). Psychiatrist Amir Levine gives us a set of tools to help us feel more secure in all our relationships, not just romantic ones, but with colleagues, friends, family and even with ourselves. This is not a fanciful book but is grounded in research and neuroscience. I believe if you follow its principles, you will in time become more secure. But any psychological work is not like rubbing on cream – it wouldn’t be enough just to read the book. You’d have to do the work and then keep up the practice. Secure can help you know yourself better, and self‑awareness is the first step towards positive change, in this case becoming more open and relaxed in all your relationships. If you can’t wait until April, my runner-up is his first book, Attached, written with Rachel Heller.

Philippa Perry is a psychotherapist. Her latest book is The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read.

Have better conversations

Chosen by Hannah Critchlow

Emily and Laurence Alison’s Rapport is fantastic at helping us to understand other people, and showing how we can work with them to increase our own cognitive power. There’s evidence that a huge part of our species’ success has been due to our ability to cooperate. We constantly take shortcuts in our information processing, accumulate biases throughout our lifetimes, and have genetic predispositions to seeing the world in different ways. But when you get a group of people together and allow them to communicate freely, it can balance out biases so they can start to see the world more accurately. And from that, we can start to solve problems and move forward in a positive way.

The authors draw on their own experiences as forensic psychologists, working in dangerous, hostile situations, and set out four personality categories – monkey, T rex, lion or mouse – each with communicative strengths and weaknesses. This provides a roadmap to understand yourself and others too. I think it’s incredibly important in the modern world that we continue to build these interpersonal skills, creating rapport even with those who think differently to us, as opposed to just hiding behind our screens.

Hannah Critchlow is a neuroscientist at Magdalene College, Cambridge University. Her new book, The 21st-Century Brain, will be published in April.

Sustain a long-term relationship

Chosen by Orna Guralnik

Stephen Mitchell was, in a way, the founder of the relational school of psychoanalysis, which is a more contemporary school of psychoanalysis – and Can Love Last? is a very useful book for couples to read. He talks openly, in accessible language, about the underlying unconscious dilemmas that love poses, the risks of vulnerability, dependency and unpredictability and the ways in which we try to avoid risk and dampen love to feel safer. It helps people get in touch with their more fundamental motivations, allowing them to be more courageous in their loving.

Rather than offering “three things you can do tomorrow”, it goes deeper. Mitchell gives engaging examples. I love that he speaks intelligently about this intense experience that we all go through; forming relationships, falling in love, struggling with it when often we feel like we don’t understand what’s happening to us. And he speaks beautifully to the tension between the need for safety and the need for adventure.

Orna Guralnik is a New York-based clinical psychologist and psychoanalyst, best known for the television show Couples Therapy.

Stop being a people pleaser

Chosen by Alex Curmi

The Courage to Be Disliked by Ichiro Kishimi is different from any other self-help book I’ve ever read, with the format of a philosopher talking to a young, frustrated student really drawing you in. Everyone can relate to being that young person trying to figure things out. And I think everyone feels like they have that older, wiser person in them somewhere too. The book is intended to introduce readers to the work of Austrian psychoanalyst Alfred Adler. He felt that at any point you can decide to change your life.

People pleasers often unconsciously take on the responsibilities of not just their own life but of other people’s, because they feel if they don’t put in that extra effort, other people are going to dislike them. Kishimi introduces the Adlerian idea of the separation of tasks, where you decide which tasks you are responsible for and then let other people get on with their own tasks.

That’s extremely liberating. Of course, the huge irony is that when you live without fear of dislike, people tend to like you much more because they intuit that you have a lot more self respect and you’re being more genuine, and genuineness and authenticity are very appealing.

Dr Alex Curmi is a consultant psychiatrist and host of the Thinking Mind Podcast.

Be happier

Chosen by Paul DolanI first encountered Oliver Burkeman’s writing when he wrote a series for the Guardian called This Column Will Change Your Life. He doesn’t take himself too seriously and I admire his self-deprecation. You can be serious and say things that are important and robust and also have some levity. Four Thousand Weeks is enjoyable to read and consistent with what I’ve always said about one of the key ways to be happier or live better, which is just to get over ourselves about stuff. Burkeman talks about the fact that we’ve got a limited amount of time, hence the title. So, never mind next week. What are you going to do this week to make it just that little bit better? Focus on the small stuff, not the big stuff, do things now rather than later, stop worrying about making next week perfect.

It’s fundamentally about happiness, because that is the ultimate achievement. It’s interesting when people say they want to be successful. What is the point of success? It’s a cliched thing to say, but it’s about the journey.

Paul Dolan is professor of behavioural science at London School of Economics. His latest book is Beliefism: How to Stop Hating People We Disagree With.

Navigate trauma

Chosen by Lisa Feldman-Barrett

George Bonanno has studied trauma in many forms for over three decades, and in The End of Trauma he challenges some conventional, outdated beliefs. Stories and case studies show that trauma is personal: it varies across people and contexts. It’s not a feature of an event, but an experience. Adverse events can happen to people and they might not be traumatised, but equally, something that would not be traumatic for many can authentically be traumatic for you. Trauma doesn’t mean “I feel really, really bad”. It means “I’m having intrusive thoughts and can’t connect with the pleasures of the moment. I’m feeling so bad that I can’t function.” Still, most people are surprisingly resilient and do not develop PTSD – even after terrible events such as 9/11, rape or war. People are distressed, they get angry, they grieve, but most can function in their everyday lives.

Bonanno also shows that resilience to trauma is rooted in how flexibly you cope. Sometimes it helps to talk about your experience, but other times it helps to distract yourself. Sometimes you should seek company, but other times it’s better to take a hot bath and go to bed, hoping tomorrow will be a better day. It’s always possible to look at the event from different angles, which ultimately gives you more choice in how to feel. Flexibility is a skill that can be learned and practised like any other. Ultimately, you have agency over how you deal with the slings and arrows you encounter in life. With agency there is hope.

Handle stress

Chosen by Robert Sapolsky

I’d recommend Dopamine Nation by a colleague of mine, Anna Lembke (a professor of psychiatry at Stanford University). I don’t recall if the word “stress” appears in the book, but it’s ultimately about that in a very meaningful way. Her focus is the biology and psychology of why our cultures leave us so empty and prone to addiction, why the more we eat, the hungrier we get. She emphasises how we, in our privileged lives in the west, have been led to believe that we should never feel pain, failure, defeat, discouragement: “everyone’s a winner”. What this does, for one thing, is make us pathetic and unprepared when it comes to really tough circumstances. She has a model according to which, in the absence of any capacity to tolerate pain and being hypersensitised to the kinds of pain that are inevitable in any life, we get a hypersensitised craving for reward that leads to addiction. The take-home message for me is to remember the consequences of having the goal of a pain-free life with no setbacks or adversity.

Robert Sapolsky is professor of biology, neuroscience and neurosurgery at Stanford University. His latest book is Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will.

Tackle narcissism

Chosen by Linda Blair

Today we tend to want to label everything, and I don’t think that’s always the most effective way to create change and wellbeing. Narcissism is a term that people love to throw around as an insult: “They’re such a narcissist.” What they actually mean is, “I don’t think they value me enough, and I don’t think they see my point of view, and for that reason they’re annoying me.” Well, guess what? That is narcissism, too. And by focusing on it, either in yourself or in others, you are simply making it worse.

To treat a diagnosis of narcissistic personality disorder, the most important thing is working on deepening and strengthening your relationships. What that comes back to is not just thinking about other people’s point of view, but getting more realistic about your own. So – like the Dalai Lama – try to think of everybody as being equally important, including yourself, and spend your time trying to understand them rather than judge. In the blink of an eye, you’ve begun to solve narcissism, either in yourself or in your tendency to call it out in others, and you will emerge happier. The Art of Happiness is a dialogue between a western psychiatrist, Howard Cutler, and the Dalai Lama and I think it’s a winner. It may have been published in 1998 but the wisdom isn’t dated and the Dalai Lama, of course, is still going strong.

Linda Blair is a clinical psychologist. Her latest book is Siblings.

Become a better parent

Chosen by Emily Oster

Thomas Phelan’s 1-2-3-Magic is an older book but it is fundamentally sensible and I think it would help a lot of people enormously. It’s a bit of a corrective to some of the more intense and exhausting parenting books we have had lately.

The intention is to give you a system, and tell you how to implement it – so it’s very no-nonsense, with a lot of worked-up examples. It feels like good, sensible advice, structured so you can be successful. The crux of it is that, when thinking about behaviour change, kids respond well to a consistently implemented system of rewards and punishments. And – maybe more importantly – if you get to a better place, family life will be easier and there will be more space for fun.

Emily Oster is professor of economics at Brown University. Her latest book is The Unexpected: Navigating Pregnancy During and After Complications.

Understand neurodiversity

Chosen by Almuth McDowall

Approaching Autistic Adulthood by Grace Liu is one of my favourite books. Grace is mixed race and a lesbian, and beautifully illuminates the intersectional perspective. She does a great job of describing her journey to adulthood and the difficulties she has experienced without sugar‑coating or judging others. Some of it makes me laugh out loud, such as her description of “neurotypical‑splaining”, as in when people who are not autistic try and tell autistic people what it is like. The book gives real-life insight into the autistic mind. It’s a great read for autistic people (“You are not alone! Here are some things for you to think about to navigate life better”) and for people who come in contact with autistic people, which given population prevalence means all of us at some point (“This is how you can respond appropriately, without patronising or belittling people”).

It’s an easy and poignant read with many anecdotes. Grace’s approach is also evidence based – she tries to address the double empathy problem: that autistic people understand each other, and neurodivergent people understand each other, but communication across the two neurotypes often results in misunderstanding. She debunks some of the myths and is honest and authentic in her writing.

Almuth McDowall is a psychology professor at Birkbeck College, London, specialising in neurodivergence research.

Maintain focus

Chosen by Oliver Burkeman

How to Focus by John Cassian, translated by Jamie Kreiner,is from a series published by Princeton called Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers. Cassian was a fourth-century Christian monk but the translation is informal, refreshing and modern. It’s about the problem of concentration and distraction, which they figured was partly because of demons but also because of the vagaries of how human attention works, which they could do something about.

First, know that distraction is a perpetual challenge, and it makes a lot more sense to just accept that. Second, prioritise having interesting things to focus on instead of the other tempting distractions that lure you away. So it’s not a self-punishing, “I will not spend an hour doomscrolling”, it’s, “how can I make sure that I am spending some of my time and my life on things that naturally draw me to them, and I prefer to do than spending all that time doomscrolling?”

The most borrowable solution offered is the idea of making a daily practice, something that you can keep coming back to, and learning to forgive yourself when your focus is less than what you would have it be. You’re still working the muscle of concentration.

There is something profound about any opportunity to glimpse that whatever torments us today might actually, in some way, be a timeless part of the human condition. I feel lifted up or supported somehow by these people. We’re all just chipping away at it and that’s why you don’t need to beat yourself up for not having done more than that.

Oliver Burkeman is a writer. His latest book is Meditations for Mortals.

SOURCE : The Guardian

Books

Children and Teens Roundup: Best New Picture Books and Novels

The Good Deed Dogs by Emma Chichester Clark, Walker, £12.99

Three very good dogs’ attempts to help others keep backfiring with chaotic consequences – until they pull off a successful kitten rescue in this exuberantly charming picture book.

Auntie’s Bangles by Dean Atta and Alea Marley, Orchard, £12.99

Everyone misses Auntie, especially the jingle of her jewellery; but eventually Theo and Rama are ready to put on her bangles and dance to celebrate her memory. A sweet, poignant picture book about loss, joy and remembrance.

Grandad’s World by Michael Foreman, Scholastic, £12.99

Jack loves spending time with his grandad, watching wildlife in the woods and round the village pond. But when rubbish pollutes the water, it’s up to Jack and Grandad to put things right in this absorbing picture book, full of soft blues and greens and the fascination of the natural world.

Jake in the Middle by Michael Catchpool, illustrated by Shanarama, Otter-Barry, £8.99

Jake lives with his bossy older sister and shoe-stealing baby brother at No 3 Maple Street, enjoying gentle, child-friendly adventures such as a trip to the city farm with his grandpa or setting up a school museum. This engaging 5+ chapter book will delight newly independent readers.

Postman Planet by Ben Davis, Gallery Kids, £7.99

Postman Planet pretends to be the best postman in the universe, but despite his moustache he’s only nine years old. Now he and his new part-robot dog assistant have to make an urgent helium delivery to the Planet of Fluffy Unicorns – but can they dodge the Space Vikings who want to steal their cargo? A laugh-out-loud, highly illustrated interstellar caper for 6+ by an author who’s also a real-life postman.

Donut Squad 2: Make a Mess! by Neill Cameron, DFB, £9.99

As Anxiety Donut goes on a mindfulness retreat and Dadnut teaches Li’l Timmy the meaning of life, everyone’s favourite glazed pastry treats are back – but the aggressively savoury Bagel Battalion have plans to banish them from their own book in this rip-roaring 7+ graphic novel sequel, just as funny, silly, clever and addictive as volume one.

The Golden Monkey Mystery by Piu DasGupta, Nosy Crow, £7.99

Aspiring doctor Roma is amazed to discover a golden monkey near her Indian boarding school, far away from its home in Assam. Despite two English children tagging along, bandits on her tail and the malign influence of a cursed jewel called the Snakestone, Roma is determined to return the monkey to where it belongs in this full-tilt, thrilling 8+ historical adventure.

The Experiment by Rebecca Stead, Andersen, £7.99

Eleven-year-old Nathan has always known that he’s from another planet, part of a long-running Earth-based experiment that seems to be coming to an end. But as Nathan’s peers start disappearing and his own family are called back to the Mothership, he begins to question everything he’s believed to be true … An imaginative, humorous coming-of-age sci-fi story for 9+ by an award-winning author.

The Monsters at the End of the World by Rebecca Orwin, illustrated by Oriol Vidal, Puffin, £8.99

Everyone knows that the monsters infesting the sea near Sunny’s tiny town are violent and terrifying – until Sunny meets one, and finds out that what everyone knows is wrong. But Seawaren’s elders won’t listen to Sunny, even though someone in the town is keeping a monstrous secret of their own. This gripping post-apocalyptic debut for 9+ emphasises empathy and curiosity as essentials even in the toughest of times.

The Night I Borrowed Time by Iqbal Hussain, Puffin, £8.99

Zubair is a seventh son, but it’s not until his granny arrives from Pakistan and gives him a strange amulet that he discovers he has the ability to time-travel. When he attempts to fix his parents’ marriage, however, Zubair finds that meddling with the past presents a lot of pitfalls in this funny, touching, thought-provoking 10+ story, richly imagined and deeply inventive.

Bottom of Form

Ghost Boys: The Graphic Novel by Jewell Parker Rhodes, illustrated by Setor Fiadzigbey, Orion, £9.99

The story of 12-year-old Black boy Jerome, who is shot dead by a police officer while playing with a toy gun, and whose ghost meets the spirit of Emmett Till in the afterlife, has now been given a hauntingly powerful graphic novel treatment, with chapters alternating between Dead and Alive. A moving, enraging version of the original novel.

Beth Is Dead by Katie Bernet, Scholastic, £8.99

What would happen to Louisa May Alcott’s March girls if one of them was murdered? A compulsive, sometimes gory reimagining of Little Women as a modern YA thriller, told from all four sisters’ perspectives.

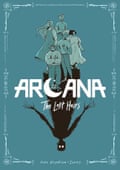

Arcana: The Lost Heirs by Sam Prentice-Jones, Hot Key, £14.99

Eli doesn’t know other witches exist until he meets the gorgeous James and is inducted into the Arcana, a magic society ruled over by the mysterious Majors. Eli and his newfound family are threatened by a curse rooted in the Arcana’s history – can they face the secrets of the past to break free of it? This whimsical, inclusive, queer debut YA graphic novel is inspired by the tarot deck.

Queen of Faces by Petra Lord, HarperFire, £16.99

In Caimor, the rich can pay to change their ailing, ageing bodies, but 17-year-old Ana is trapped in a dying male form that will kill her if she doesn’t trade it for a better one. Her last hope of survival is to become an assassin for Caimor’s elite school of magic – but as the terrifying dark mage Khaiovhe incites a gathering rebellion, Ana’s missions become steadily more dangerous and confusing, forcing her to re-evaluate her loyalties and beliefs. A hugely ambitious, wholly riveting 14+ fantasy debut.

The Guardian

Books

inside the Ozempic revolution

Few aspects of being human have generated more judgment, scorn and condemnation than a person’s size, shape and weight – particularly if you happen to be female. As late as 2022, the Times’scolumnist Matthew Parris published a column headlined “Fat shaming is the only way to beat the obesity crisis” in which he attributed Britain’s “losing battle with fat” to society’s failure to goad and stigmatise the overweight into finally, shamefacedly, eating less. The tendency to equate excess weight with poor character (and thinness with grit and self-control) treats obesity as a moral as well as physical failing – less a disease than a lifestyle choice.

One of the great strengths of Reuters journalist Aimee Donnellan’s first book is its insistence on framing the discovery of the new weight-loss drugs within the fraught social and cultural context of beauty norms, body image and health. For those who need them, weekly injections of Ozempic, Wegovy or Mounjaro can be revolutionary. Yet for every person with diabetes or obesity taking the drugs to improve their health, others – neither obese nor diabetic – are obtaining them to get “beach-body” ready, fit into smaller dresses, or attain the slender aesthetic social media demands of them. Small wonder some commentators have likened the injections to “an eating disorder in a pen”.

Donnellan opens the book with a case in point, a poignant interview with “Sarah”, a 34-year-old marketing executive from Michigan. She recounts a summer of unprecedented success at work – suddenly being included in important meetings, being assigned new management responsibilities and receiving a raise. Yet nothing had changed about her behaviour at work. It was her appearance – after six months on Ozempic – that had undergone a metamorphosis. In the eyes of her employers, shedding five stone (32kg) of weight had transformed her worth: Sarah mattered more because she weighed less.

Like all great tales of scientific discovery, the weight loss saga is rich in serendipity, rivalry and obsession – all of which Donnellan recounts with relish. Wonderfully, it includes a starring role for the only venomous lizard in the US, the Gila monster, though I will refrain from spoilers here. Another key protagonist is Svetlana Mojsov, a young Macedonian immigrant to the US who arrived at New York’s Rockefeller University in 1972 to do post-grad chemistry. (Today, one imagines, ICE would probably deport her.) At this time, the causes of obesity were seen as self-evident – eating too much and exercising too little – and therefore unfit for serious scientific inquiry. Mojsov disagreed. She was fascinated by why some people seemed to feel sated earlier than others, or metabolised food more quickly. Her research – for which she is tipped to win a future Nobel prize – successfully engineered a synthetic version of a natural hormone, glucagon-like peptide (GLP-1), which helps control blood sugar.

Scientists at Danish pharma giant Novo Nordisk seized on GLP-1 as a potential new treatment for diabetes. Decades of effort at last culminated in a drug, semaglutide, that people with diabetes could administer once weekly, unlike multiple daily injections of insulin. But the drug trials revealed something unprecedented. Not only did semaglutide control blood sugar beautifully, it caused participants to lose up to 20% of their body weight, seemingly without even trying. Novo Nordisk had stumbled across the holy grail – a safe chemical treatment for obesity that worked to astonishing effect. As word of the miracle jab leaked, celebrities began to seek it out. When a newly svelte Oprah Winfrey told her podcast fans that taking the drug was the cause, suddenly everyone was clamouring for Ozempic. That this had occurred in her lifetime, said Winfrey, “felt like relief, like redemption, like a gift”. It was certainly a gift to Novo Nordisk, whose market value is now, thanks to Ozempic, bigger than the entire GDP of Norway.

Commendably, Donnellan is careful not to treat the GLP-1 drugs an unalloyed good. She addresses their side-effects, such as severe nausea, and their use by non-obese people to the potential detriment of their health. The one omission is that she doesn’t dig into what is surely the most intriguing aspect of weight-loss drugs: incredibly, scientists simply don’t know why they excel at treating obesity, beyond the fact that GLP-1 receptors are present in the brain. It appears that saturating the brain with abnormally high levels of the hormone dials down people’s craving for food. A lifetime of incessant chatter about eating is dampened. Restraint becomes easy, effortless. Does this mean drugs like Ozempic will be licensed in the future to treat drug, alcohol, gambling and sex addiction? What would that do to our concept of free will? Ozempic is a miracle drug, a rebuke to a century of condemnation of those who are obese, and a profound challenge to the very definition of what it means to be human. Watch this space.

-

Discover2 months ago

Discover2 months agoIs February 2026 really a once-in -283-years MiracleIn?

-

Football3 months ago

Football3 months agoAlgeria, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire win AFCON 2025 openers

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoBascom Palmer Eye Institute Abu Dhabi and Emirates Society of Ophthalmology Sign Strategic Partnership Agreement

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoNMC Royal Hospital, Khalifa City, performs rare wrist salvage, restoring function for young patient

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoEmirates Society of Colorectal Surgery Concludes the 3rd International Congress Under the Leadership of Dr. Sara Al Bastaki

-

Health4 months ago

Health4 months agoBorn Too Soon: Understanding Premature Birth and the Power of Modern NICU Care

-

Football4 months ago

Football4 months agoGlobe Soccer Awards 2025 nominees announced as voting opens in Dubai

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoDecline in Birth Rate in the UAE